Ever since collections of cells harmoniously sludged together to form the first gloopy, multicellular organisms, we trudged from the oceans in search of answers. And, upon evolving into the enigmatic, knowledge-craving super-sleuths, that we are today (politicians excluded), man has asked a series of seminal questions, relating to the universe. What is the meaning of life? Why is this divine being telepathically barking orders into my head (if you belong to this camp, forget I mentioned evolution) and, most profound of all, where is my next video game coming from?

There’s a mind-boggling catalogue of games out there, waiting to be played. I, for one, have ridiculously bloated Steam and GOG accounts, stuffed to the rafters with games, diverse in genre; I just can’t help it, I become a frenzied, salivating loon, greedily snapping up the digital deals and becoming a shambling vagrant, during the holiday seasons, whilst I pay back the money. So, when presented with the opportunity, which games should I pay for, and which games should I play?

There’s a mind-boggling catalogue of games out there, waiting to be played. I, for one, have ridiculously bloated Steam and GOG accounts, stuffed to the rafters with games, diverse in genre; I just can’t help it, I become a frenzied, salivating loon, greedily snapping up the digital deals and becoming a shambling vagrant, during the holiday seasons, whilst I pay back the money. So, when presented with the opportunity, which games should I pay for, and which games should I play?

This presents an interesting starting point, when considering our primary options; the blockbuster game vs. the indie game. As of late, I tend to purchase more indie games than I do blockbuster, for a number of valid reasons; the first being financial. When people investigate a product’s intrinsic value, they often do so with an economic mindset.

So, when I look at Battlefield 4, say, and compare it to Sir, You Are Being Hunted, I see that both have various plus points, as well as negatives. Then, I move onto one of the top, deciding factors, the price. From the date of writing, Battlefield 4 Deluxe is retailing at a, not-so-healthy, $69.99 from Origin. Sir, You Are Being Hunted is currently pre-ordering at $20.00. So, I could also pre-order Among The Sleep ($20.00) and Spy Party ($15.00) and still have a $14.99 surplus for when Ether One, Path of Exile or Prison Architect is released, unto the world. The follow-up question must then be, is Battlefield 4 (or any singular, blockbuster title, for that matter), in terms of entertainment value, greater than three to four indie games combined? This is empirically difficult to evaluate and down to subjective opinion and preference, but it does get you thinking.

Bottom Line Bawling

So, why must customers renegotiate their mortgage payments to buy today’s modern games? At a time when EA is bellyaching over earning a paltry revenue of $1.2 billion (instead of $1.37 billion), for this quarter, part of the problem could lie with extreme publishing costs and profits. This matter raises a moral contention. Should I support developers under the reigns of greedy, soulless publishers? If the motivating factor for a publisher lies solely in making exorbitant fiscal returns, then, the statement could be posited, fulfilling this objective might be at the expense of quality, content and customer service. I fully appreciate that the developers have significant creative input to their projects, but you would have to be naïve to think that the inevitable toeing of the corporate line doesn’t affect the final outcome of a game’s development cycle. How many corners is a developer willing to cut when their keepers string a noose around their neck and ask them to dance to their tune?

Indeed, we’ve already witnessed the “persuasive” workings of many publishers, pontificating over the financial margins and the bottom-line. Dead Space 3 and the latest Tomb Raider reboot serve as prime examples of publishers warranting unreasonable returns from products. Back in June 2012, President of EA Labels, Frank Gibeau, inadvertently offered an unadulterated picture of the toxic involvement of his own industry, arguing that the Dead Space franchise’s many changes, including a focus on action-orientated gameplay and inclusion of cooperative mode, were for the sake of “broader appeal”. His honesty knew no bounds, as his splurge continued; “5 million copies” of the new Dead Space were needed to be shifted, otherwise it becomes, “quite difficult financially”. I feel it important to note, at this point, that DS3’s predecessors sold much less than this figure, neither of which were limited by Origin exclusivity (who’s doing the math here?).

A year down the line and EA CFO, Blake Jorgensen, recently stated that Dead Space 3 and Crysis 3 sales figures didn’t meet expectations. Lo and behold, EVP of EA Games Label, Patrick Soderlund, recently announced that further DS iterations are not currently in the works, citing the development team to be, “… working on something else that you and other gamers will be happy with.” Under the circumstances the afore-mentioned sales had indeed exceeded company predictions, and sold the Earth’s weight in DS3 copies, I would have wagered my own manhood on the immediate inception of another Dead Space game.

Dancing with the Devil of Dollars

It obviously isn’t beyond the realm of possibility that, not only do financial considerations influence a game’s structure and content, financial outcomes affect a studio’s likelihood of survival in the industry, based upon the machinations of its publishing overlords. Activision killed Bizarre Creations, Eidos ruined Looking Glass Studios, EA crushed Westood, Pandemic, Bullfrog, Origin Systems… well, the list could go on, until I turn a strange, purple color, but you get my point. And, when 3.4 million copies sold for a Tomb Raider reboot isn’t enough by a publisher’s standards, you can’t help but feel concern for a developer’s future.

It obviously isn’t beyond the realm of possibility that, not only do financial considerations influence a game’s structure and content, financial outcomes affect a studio’s likelihood of survival in the industry, based upon the machinations of its publishing overlords. Activision killed Bizarre Creations, Eidos ruined Looking Glass Studios, EA crushed Westood, Pandemic, Bullfrog, Origin Systems… well, the list could go on, until I turn a strange, purple color, but you get my point. And, when 3.4 million copies sold for a Tomb Raider reboot isn’t enough by a publisher’s standards, you can’t help but feel concern for a developer’s future.

But, if a publisher can kill a developer, outright, what do they do when in partnership? When elaborating upon the pitfalls of industry financing protocols, former Ubisoft Associate Producer, Yann Suquet, observes the two parties:

He goes on to paint a vivid image of the milestone system, a series of contractually-imposed objectives and deadlines, used by a publisher to encourage progress. Suquet notes two obvious problems with this arrangement. Firstly, a studio’s overheads don’t necessarily stack up with the revenue received from the publisher. So, if a hamstrung developer is strapped for cash, the publisher can capitalize, by withholding finances until certain milestones are amended or added. Secondly, it compromises a studio’s independence and creativity. This opens up the flood gates, allowing pushy publishers, who know little about game design, to assume control. Aside from this, artificial deadlines can potentially lead to a game feeling rushed, affecting content and/or quality.

In addition, an endless slew of, decidedly less than exemplary, deals continue to be struck behind closed doors, to this day. Many publishers seek to instill punitive regimes, deterring failure of any kind, by incorporating clauses into the contractual agreements of their development teams. Perfunctory, Metacritic score targets are a sorry sign of the times, recklessly brandished as a narrow-minded litmus test of performance, and a publisher’s underhanded means of depriving hard-working developers of their entitled bonuses and royalty payments. Shockingly, these arbitrary schemes are now mandated as part of the hiring process, by certain employers, and have been used as the cornerstone of publisher-developer negotiation, in condemning another studio’s work, to bring about more profitable terms and conditions.

And then, there’s the development time frame. We’ve all heard of zombified programmers, hooked up to IV drips of Red Bull, working their bloody fingers to the bone, and pulling unpaid all-nighters, just to meet the deadlines thrust upon them. A disillusioned spouse of an EA employee, Erin Hoffman, substantiated these concerns. In an online post, during 2004, she described the abhorrent working conditions, which sound not too dissimilar to that of a North Korean shoe factory, during a Kim Jong Un inspection; 12 hour days, 7 days a week, with no overtime, no compensation, no sick leave and no vacation, it’s astonishing that legal ramifications are not rife. It seemed the lid had been well and truly lifted, and a string of similar allegations were issued from other workers’ spouses, enrolled at Rockstar San Diego (2010) and 38 Studios (2012).

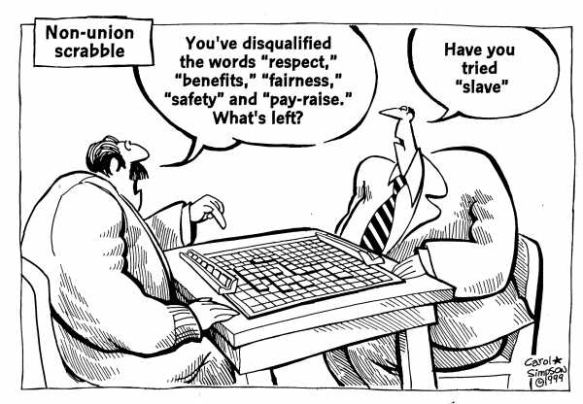

But, let’s face it, this reprehensible treatment is hardly surprising when considering game developers belong to one of the rare industries, which lacks union representation. The unsavory nature of this impugnable arrangement was unequivocally demonstrated when 100+ developer employees, who’d contributed their creative efforts towards the production of L.A. Noire, were surreptitiously excluded from the credits; this is an act, which violates IGDA Game Crediting Guidelines. However, no unions, no recourse.

It bears note, some of these issues may be studio-inflicted, whilst others may be publisher-inflicted. Professional employees are, quite understandably, unwilling to stick their heads above the parapet for fear of facing redundancy and litigation, which could materialize from prior signature of non-disclosure documents. Therefore, to date, these complications make it remarkably difficult to get an inside picture of the working conditions under some of the major publisher-developer partnerships. Recently, however, Hoffman asserts that conditions under EA have improved markedly; even if you’re no fan of John Riccitiello’s legacy, this is something to be proud of.

Indie developers don’t have the same restraints imposed upon them, as they are not in receipt of financial backing from a bunch of bean-counting creativity-crushers. Even when taking into account the introduction of Kickstarter campaigns, these low-key developers are beholden only to the consumer. In contrast, the so-called “publisher-developer” relationship has a tendency to drive a disconnect between the studio and the very people they should be trying to impress (the customer), as they, instead, chase the fleeting desires of their publisher. There’s no devil on the shoulders of the independents asking about multiplayer gameplay, set pieces or contrived plot devices and they’re able to freely explore all intended avenues, without fear of contractual barriers or threats of backing being pulled. They acknowledge a specific target audience and tailor their efforts to a niche area, rather than pointlessly branching out, in a vain attempt to generate “broader appeal”. Indie games are priced more competitively, and appear in a great many sales. On the surface, indie developers seem to display less greed. Take the Humble Bundle, where the customer purchases a selection of games and determines how much money they put in and its split between the creators, Bundle organizers and a chosen charity; consider this, since Humble Bundle’s inception, only one major publisher added their wares to an event (THQ), and only during a period of financial crisis.

[In Part II, we explore how overwhelming, publisher power stifles creativity and evolution of the industry, as well as the speculative development tactics, adopted by the big execs, based upon movie industry models, and the eternal litigation woes between publishers and developers]

Hi Samuel. You raise a very good point. Throughout the three parts of the opinion piece, I have primarily focused upon many of the disadvantages of big, overbearing publishers, dabbling in AAA game design and production. I whole-heartedly concede, on the flip-side, there are also evident disadvantages to independent game developers and their business practices. A case in point, we have recently observed Double Fine’s mismanagement of their Kickstarter-funded game, Broken Age; as the beneficiaries of 3 million dollars (over 8 times the original financial goal), Double Fine’s request for additional funding, alongside their intention to split the game into two separate parts, is arguably the end-result of an over-zealous development team, who might have benefited from more stringent regulation (something a publisher could have offered). Indeed, as you alluded to, Fez’s development cycle experienced significant hurdles, including persistent delays and a spate of legal issues between the company partners.

I think, for the sake of objectivity and balance, I would like to create a devil’s advocate post, where I draw attention to the perils of independent development, and explore the good that publisher-developer relations can offer, when executed sensibly. Thank you very much for the idea, and thank you for reading!

Pingback: Epic EVE battle, Critical games criticism, indie developer self-publishing | COOL MEDIUM